Body and Spirit

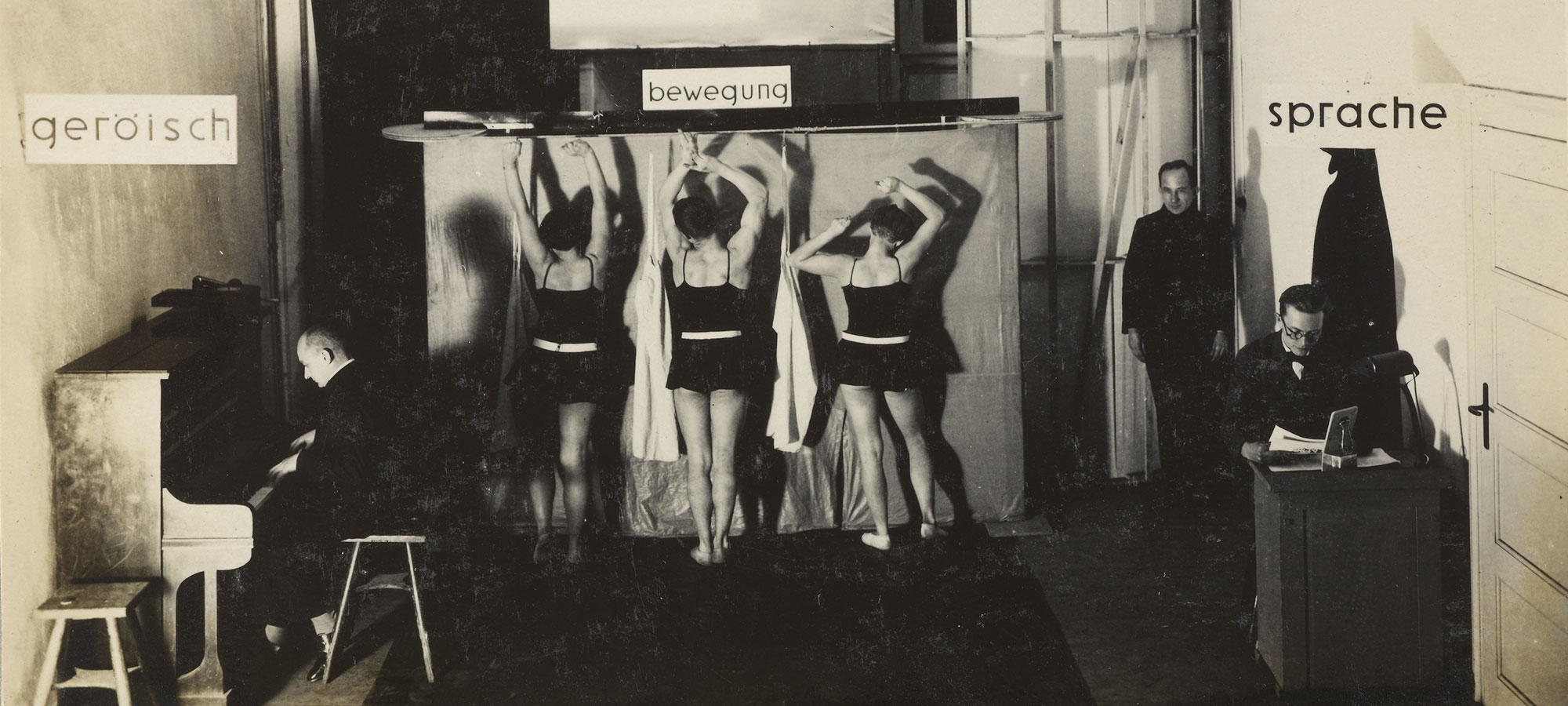

Fig. 52. Geröisch, Bewegung, Sprache (Sound, movement, speech), Irene Bayer-Hecht, ca. 1923. Gelatin silver print. 8.3 x 13.3 cm. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 85.XP.260.14

If new ideas are to adopt artistic form, then corporeal, sensual, spiritual, and intellectual powers and abilities must be equally ready and cooperating.1

Johannes Itten’s conviction that students at the Bauhaus should be educated “in their totality as creative beings” was in harmony with the unification of spiritual and material impulses described in the Bauhaus manifesto. The founding faculty at the Bauhaus were united in their conviction that the project of building the new artist should be driven by artistic experimentation and spiritual striving. Only a holistic education that considered mind, body, and spirit could prepare students to create the total work of art (Gesamtkunstwerk).

Fig. 53.

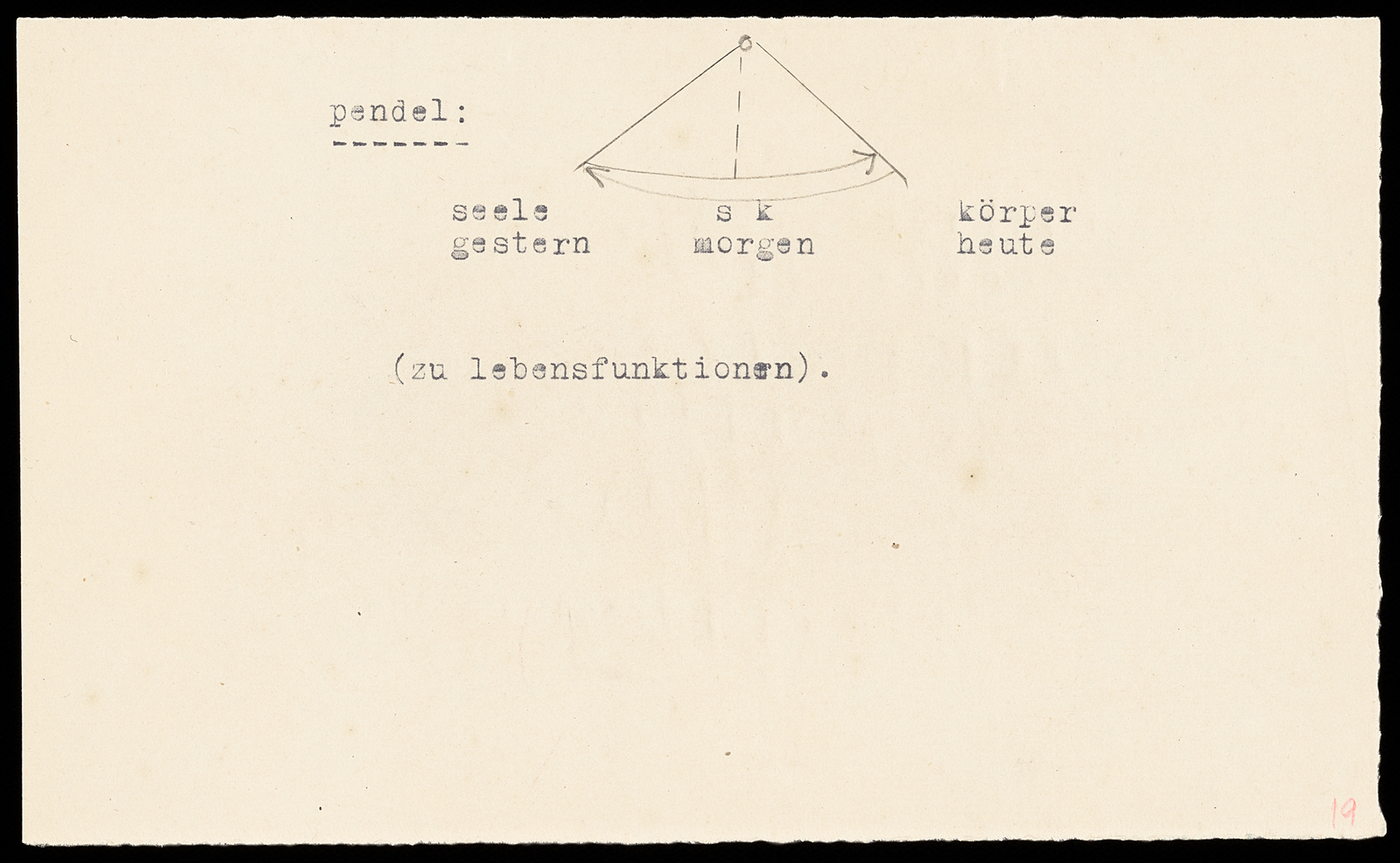

Fig. 53.Vassily Kandinsky, who taught from 1922 until the school’s closure in 1933, illustrated the relationship between body and spirit in the diagram of a pendulum (fig. 54). The pendulum swings from body to spirit and back again in eternal fluctuation. Only by working between the polarities of body and spirit can the ideal future be forged in an interstitial space on the diagram, which Kandinsky labeled “tomorrow.”

Kandinsky’s attitude was emblematic of the blend of physical work and spiritual striving that flavored the Bauhaus curriculum during its years in Weimar. This duality persisted in certain courses even after the school’s relocation to Dessau in 1925.

Classes began with a ritual meant to prepare both body and spirit for the act of creative production: the recitation of a poem, the singing of a song, or the rhythmic repetition of gymnastic exercises.

Itten recalled that during the Weimar period, all masters began classes with a ritual meant to prepare both body and spirit for the act of creative production. These exercises might include the recitation of a poem, the singing of a song, or the rhythmic repetition of gymnastic exercises. Itten explained:

The training of the body as an instrument of the spirit [Geist] is of great importance for the creative human being. How can the hand express a characteristic sensation in a line if hand and arm are cramped? The fingers, the hand, the arm, the whole body can be awakened through relaxation, strengthening, and sensitization exercises.2

Fig. 55.

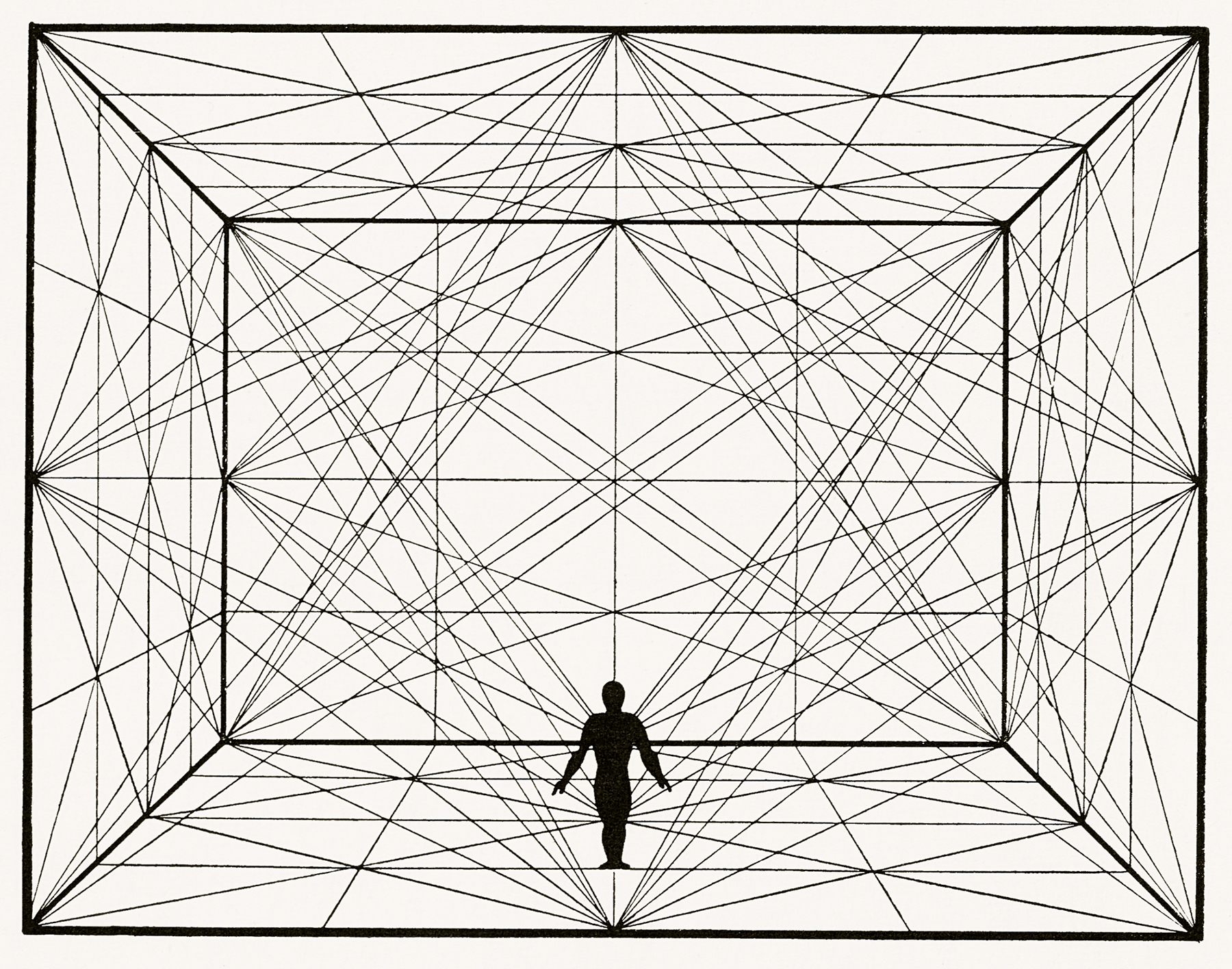

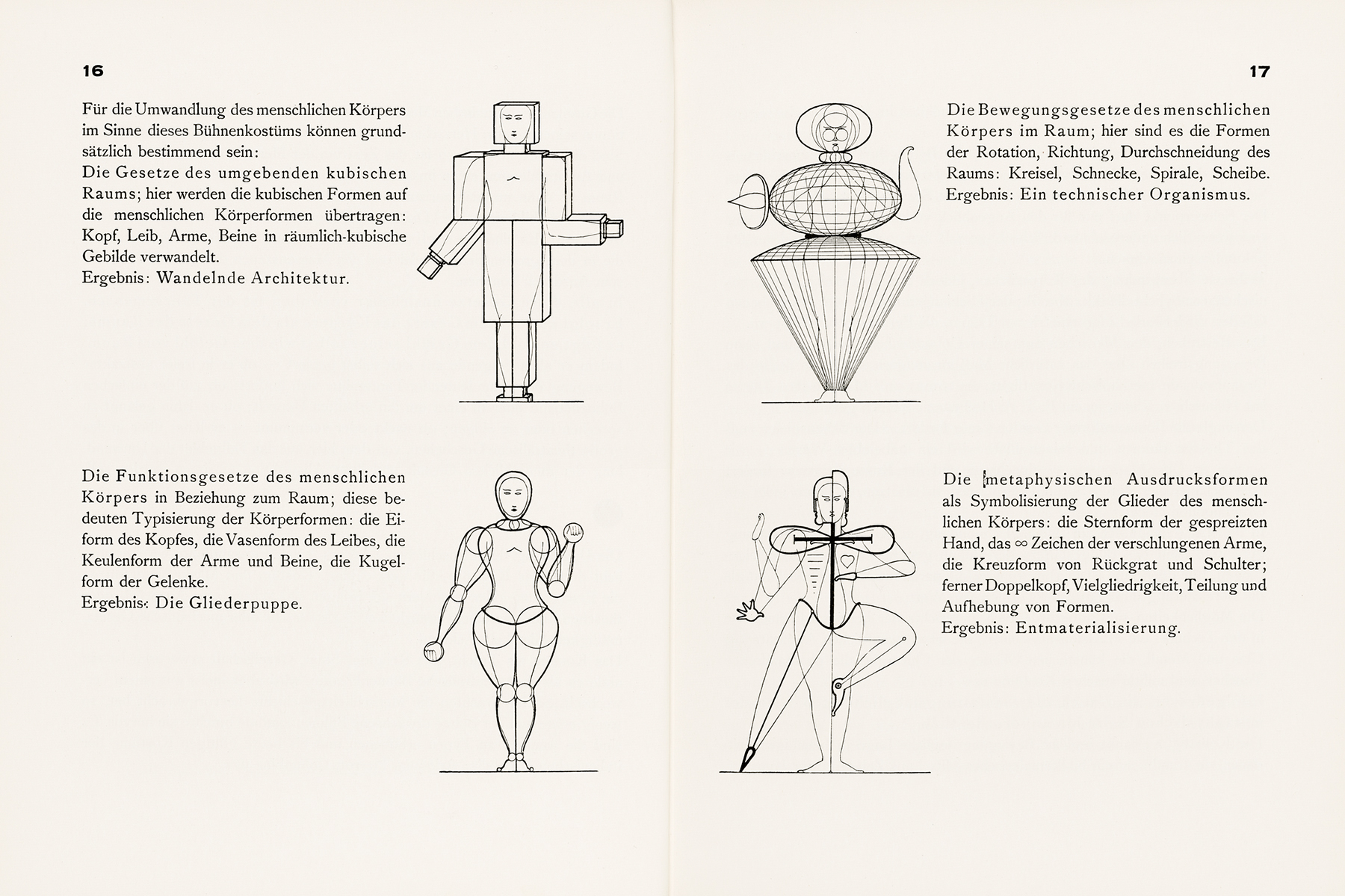

Fig. 55.Although belief in the necessity of a holistic education of mind, body, and spirit was integrated into all exercises and workshop assignments at the early Bauhaus, the embodiment of this philosophy was best illustrated through ambitious artistic projects forged through a synthesis of the arts. Architecture and theater for example required the orchestration of form, color, wood, metal, fabric, and glass in advanced combinations, both spatially and in relation to the human body. As a result, the study of the physical body in the Life Drawing class paired with the far less tangible training of the human spirit was an essential component of the Bauhaus curriculum.

Notes

- Johannes Itten, Mein Vorkurs am Bauhaus (Ravensburg: Otto Maier Verlag, 1963), 11. (German translation: Wenn neue Ideen künstlerische Gestalt annehmen sollen, müssen körperliche, sinnliche, seelische und intellektuelle Kräfte und Fähigkeiten gleichermaßen bereit sein und zusammenwirken. Diese Einsicht bestimmte weitgehend Stoff und Methode meines Bauhaus-Unterrichts. Es galt, den Menschen in seiner Ganzheit als schöpferisches Wesen aufzubauen.) ↩

- Ibid., 12. (German translation: Die Schulung des Körpers als eines Intrumentes des Geistes ist für den schöpferischen Menschen von großer Bedeutung. Wie soll die Hand in einer Linie eine charakteristische Empfindung zum Ausdruck bringen, wenn Hand und Arm verkrampft sind? Die Finger, die Hand, der Arm, der ganze Körper können geweckt werden durch Entspannungs-, Kräftigungs- und Sensibilisierungsübungen.) ↩

Animate the total work of art.

Create a performance inspired by Schlemmer’s The Triadic Balletnavigate_next| words