Architecture

At the Bauhaus, Walter Gropius sought to facilitate collaboration between masters and apprentices and between artists and designers in pursuit of a unity of the arts, with “the building of the future” as the “ultimate goal.”1 In early 1920 an opportunity to realize this vision presented itself. Adolf Sommerfeld, a lumber mill owner, building contractor, and real estate developer specializing in timber structures, commissioned the architect and his partner Adolf Meyer to design a house for Sommerfeld’s family in the south of Berlin. Gropius recognized the opportunity to bring the various workshops together in its design, which, in keeping with his postwar romantic vision, took inspiration from a rustic log cabin, foregrounding and celebrating the use of wood.

Fig. 74.

Fig. 74. Fig. 75.

Fig. 75.Gropius afforded an explicitly spiritual quality to the material, arguing that “wood is the building material of the present” precisely because “wood is the original building material of men.”2 Despite the apparently primitive association, Gropius and Meyer employed timber in an innovative fashion. The Sommerfeld House was erected quickly and economically owing to the use of Sommerfeld’s patented construction system, which layered relatively advanced thermal insulation materials between factory-cut, interlocking timber.

The Sommerfeld House represented nothing less than an actualization of the “total work of art” ideal set forth in the school’s program.

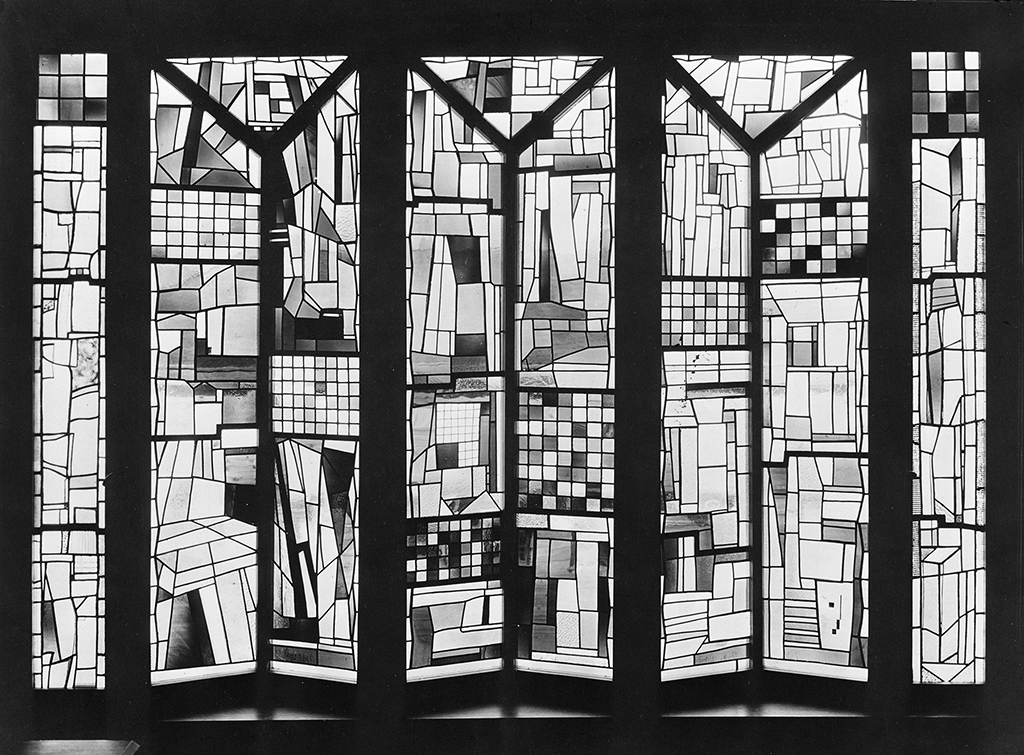

Fig. 76.

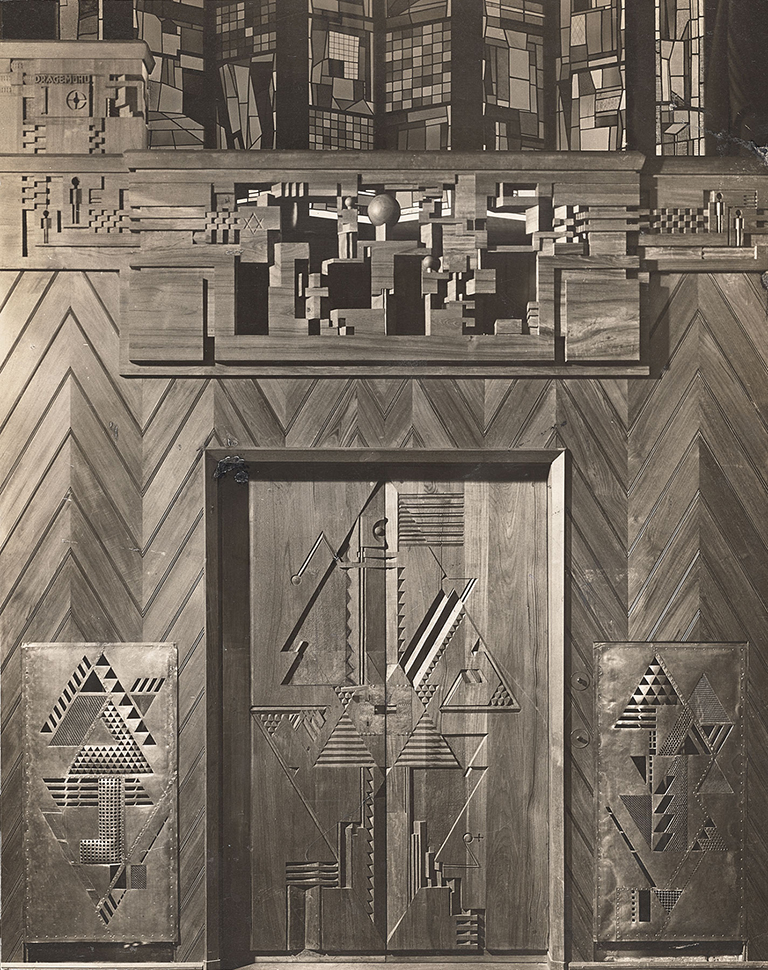

Fig. 76.On the interior of the house, the work of the various Bauhaus workshops was on full view. Josef Albers, then a student, designed a large stained glass window above the staircase (fig. 76). The crystalline motifs of Albers’s design were reflected in the wood ornament carved by Joost Schmidt, a student who would later become director of the sculpture workshop. Schmidt’s carvings clad the walls, the banisters, the doors, and the joists on both the interior and the exterior of the house with crystalline geometries—triangles, in particular—Stars of David, human figures, sawmills and other machinery, and even the names of cities where Sommerfeld had business dealings (fig. 77).

Fig. 77.

Fig. 77.Dörte Helm, a student in the weaving workshop, designed a large curtain for the interior with a similar geometric ornamental language. Marcel Breuer, also a student at the time, designed a set of wooden tables and chairs. The apprentice Hinnerk Scheper, later to become junior master and director of the wall-painting workshop, devised the scheme for interior paint color.

Other elements such as light fixtures and radiator covers were designed in the metal workshop, and rugs and wall hangings in the weaving workshop. With the conspicuous exception of the ceramics workshop, all were involved in the design and realization of the Sommerfeld House. This represented nothing less than an actualization of the “total work of art” (Gesamtkunstwerk) ideal set forth in the school’s program two years earlier.

The building’s completion in 1921 was met with great fanfare. A roof-raising ceremony with several hundred guests was held in December 1920 and featured a bonfire by Adolf Meyer, a choral recitation, and a procession, signaling the cultural and spiritual importance of this new architectural vision.

Notes

- Walter Gropius, Programm des Staatlichen Bauhauses in Weimar, trans. Katherine Rochester (Weimar: Staatliche Bauhaus, April 1919), n.p. ↩

- Walter Gropius, “Neues Bauen,” in Der Holzbau, supplement to Deutsche Bauzeitung 2, 1920, quoted in Barry Bergdoll, “Bauhaus Multiplied: Paradoxes of Architecture and Design in and after the Bauhaus,” in Bauhaus 1919–1933: Workshops for Modernity (New York: MoMA, 2009), and in Wolfgang Pehnt, “Gropius the Romantic,” The Art Bulletin, vol. 53, no. 3 (September 1971), 384. ↩