Esoteric Thought

The drive to fundamentally reconceive art education at the Bauhaus was part of a larger impulse to rebuild after the devastation of the First World War. Itten recalled that students arrived with considerable war trauma and insatiable spiritual hunger:

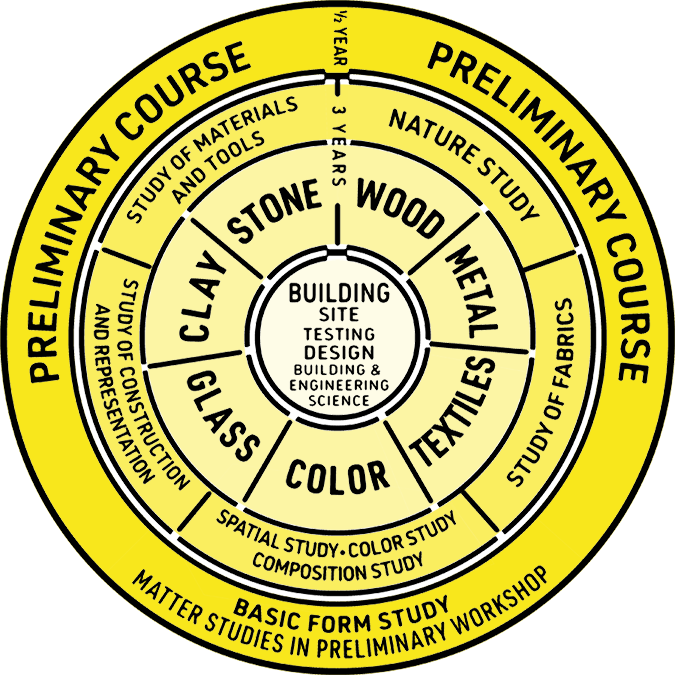

Fig. 56.

Fig. 56.The horrible events and shattering losses of war introduced confusion and helplessness in all areas. Endless discussions and fervent striving for a new spiritual identity prevailed among the students.1

Students arrived with considerable war trauma and insatiable spiritual hunger.

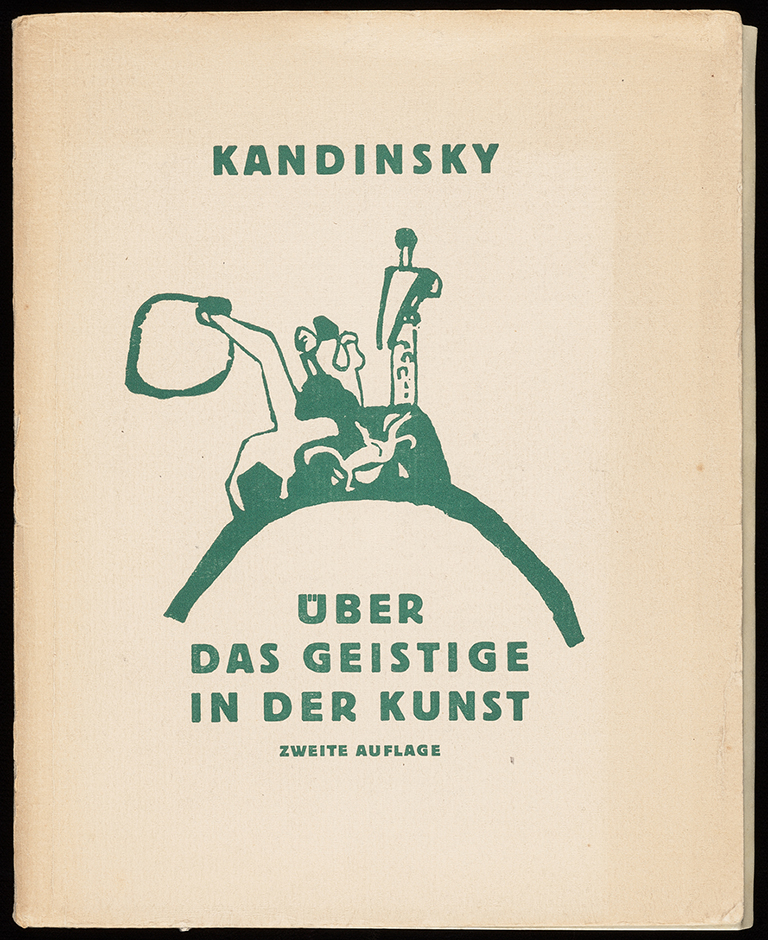

These students found compatriots among the Bauhaus faculty. In 1910 Vassily Kandinsky had published On the Spiritual in Art, a book that outlined a renewal in the arts congruent with spiritual rebirth. This modern renaissance would be led by artists of true genius who, thanks to their exceptional sensitivity toward the internal resonances of form and color, would become quasi-spiritual conductors of a new visual symphony. In this context, Gropius’s metaphor of a crystal cathedral, where art and craft would finally be united, made perfect sense.

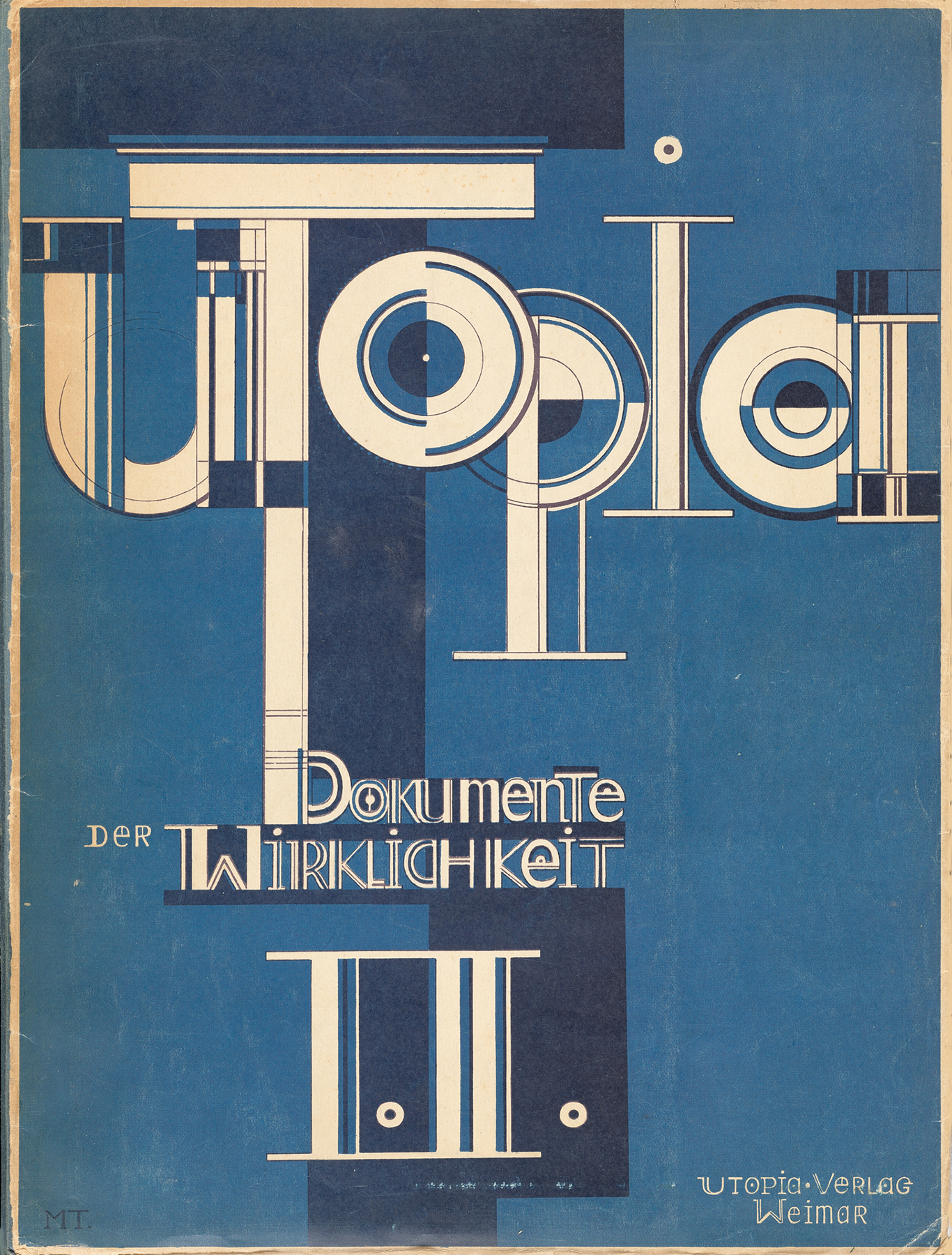

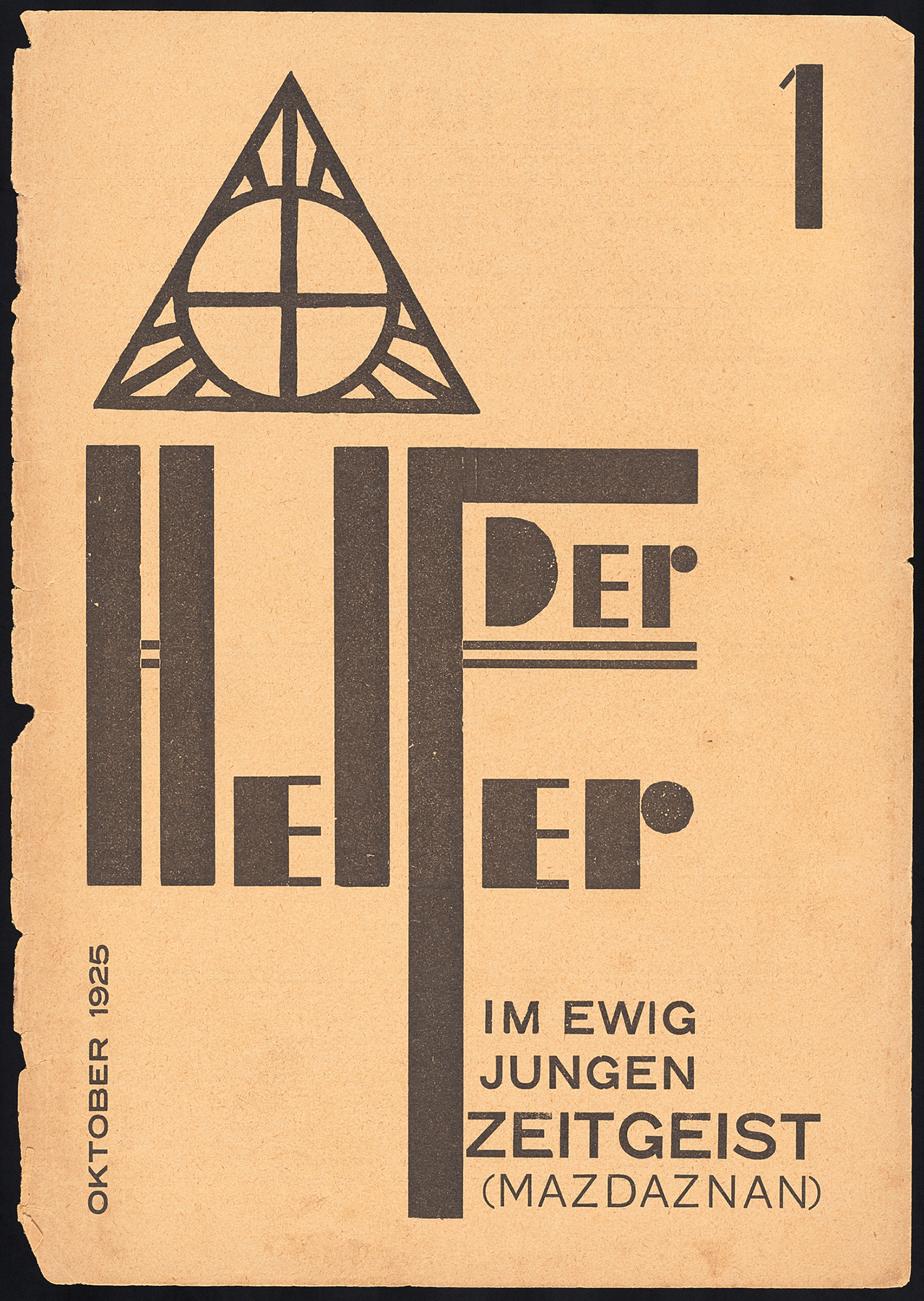

Fig. 57.

Fig. 57.However, the unity of art and craft alone was not sufficient to heal the trauma of war. Spiritual work anchored in daily rituals was also crucial. “We searched for the foundations of a new way of life [Lebenspraxis],”2 wrote Itten, who found them in a religious movement called Mazdaznan. Inspired by Western impressions of eastern philosophy, Mazdaznan dictated a strict vegetarian diet, a shaved head, special garments, and a series of gymnastic and breathing exercises meant to purify the body for spiritual insight. It also dabbled in theories of evolutionary and race-based progress, which interpreted human history as an arc from East to West, culminating in the achievements of white European men.

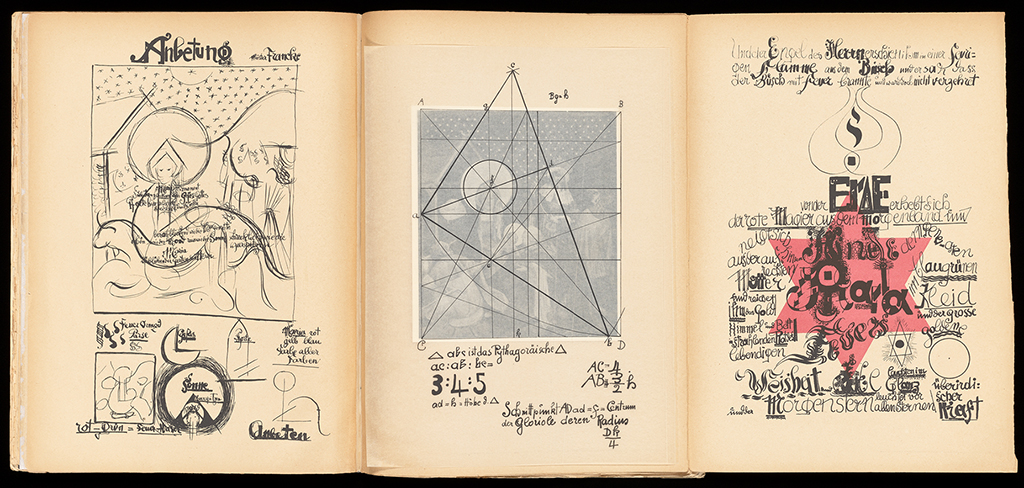

Fig. 58.

Fig. 58. Fig. 59.

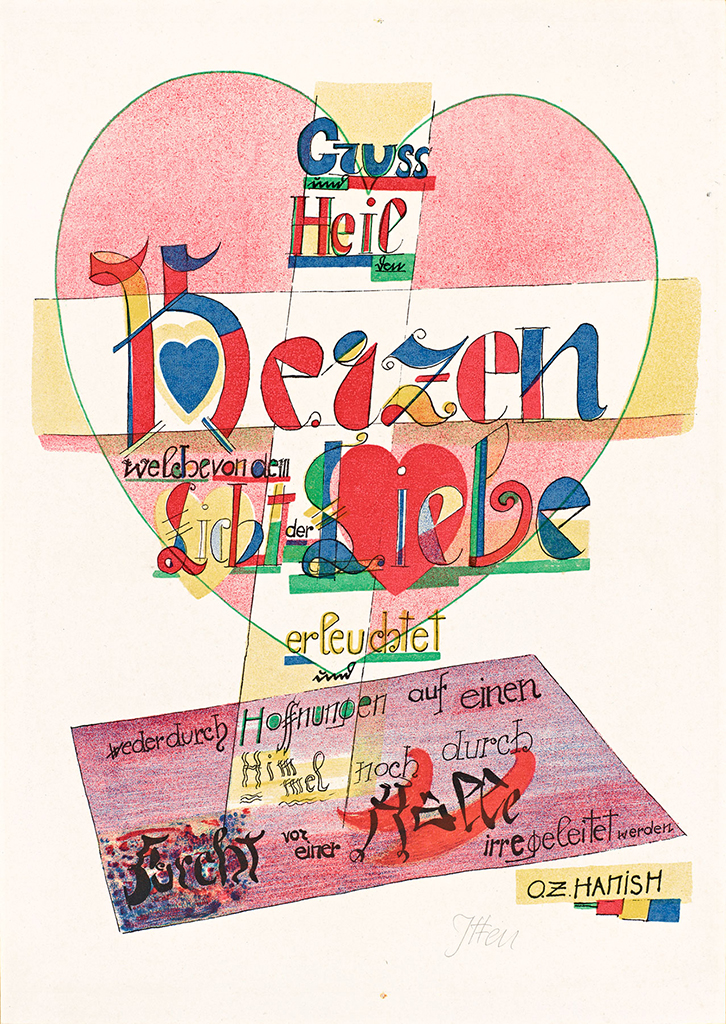

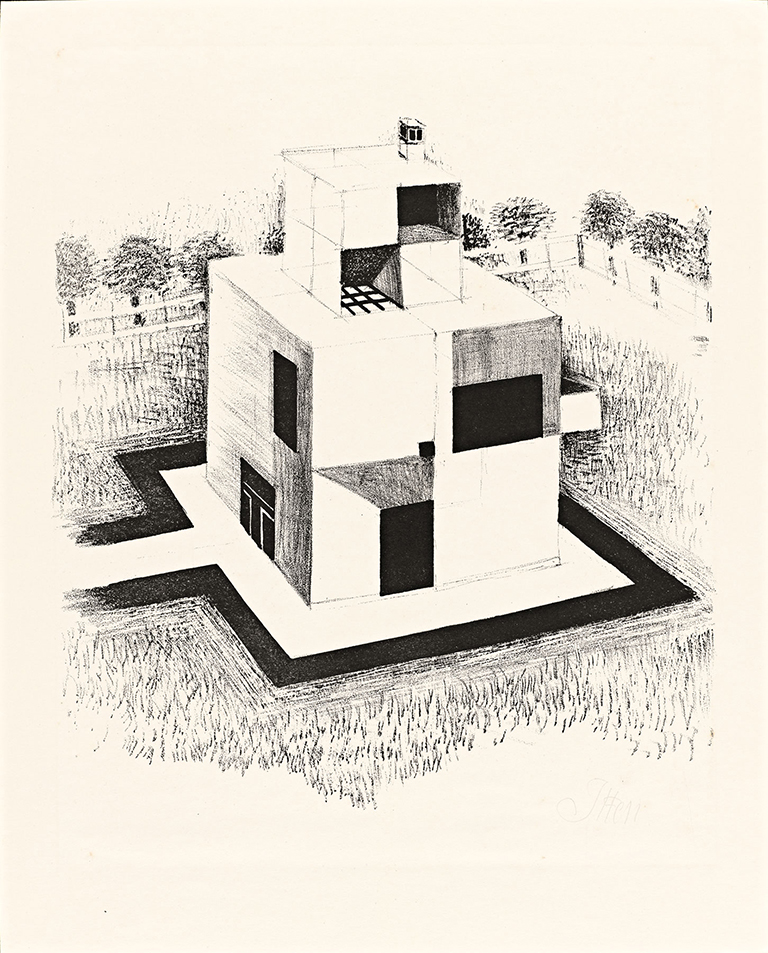

Fig. 59.Two lithographs by Itten included in the first Bauhaus portfolio highlight the opposing messages of the Mazdaznan philosophy: The first (fig. 60) embellishes an aphorism by O. Z. Hanish, the founder of Mazdaznan, that calls for humanity to “greet and hail the heart illuminated by love.” The second print (fig. 61) shows “the house of the white man,” an awkward cubic construction meant to symbolize the pinnacle of modern dwelling. In this way, claims for universal love clashed with hateful messages of white supremacy.

Fig. 60.

Fig. 60. Fig. 61.

Fig. 61.As was often the case in life-reform movements, Mazdaznan—indeed, the Bauhaus more generally—contained myriad contradictions, which must be carefully considered for how they complicate understandings of Western art, history, and current social values.

Notes

- Johannes Itten, Mein Vorkurs am Bauhaus (Ravensburg: Otto Maier Verlag, 1963), 11. (German translation: Die fuchtbaren Geschenisse und die erschütternden Verluste des Krieges hatten auf allen Gebieten Wirrwarr und Ratlosigkeit gebracht. Unter den Schülern waren uferlose Diskussionen und eifriges Suchen nach einer neuen geistigen Haltung.) ↩

- Ibid., 12. (German translation: Für uns suchten wir nach Grundlagen einer neuen Lebenspraxis.) ↩