Form and Color

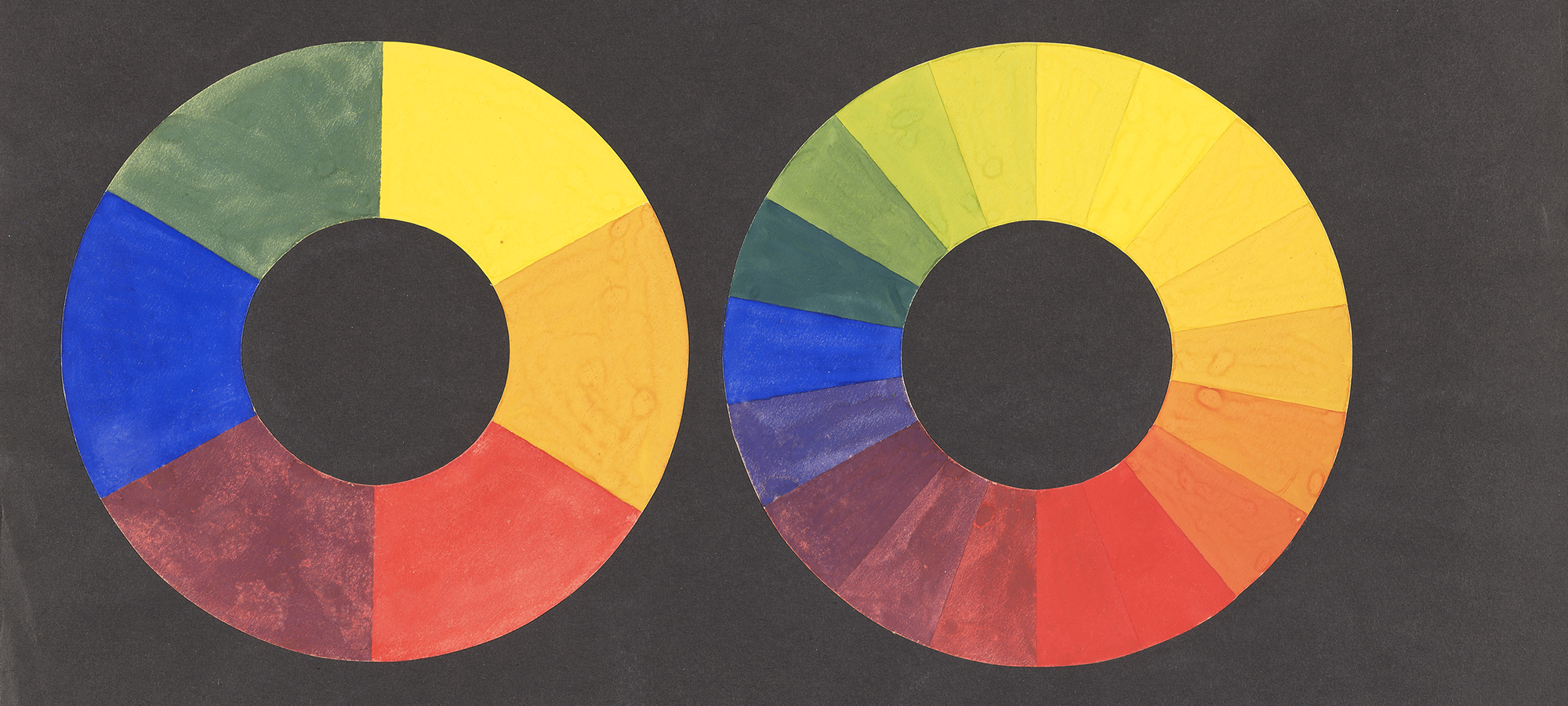

Fig. 15. Color wheel for Vassily Kandinsky’s Preliminary Course, Gerd Balzer, 1929. Gouache on paper, pasted on black paper. The Getty Research Institute, 850514

The end and aim of all artistic endeavor is liberation of the spiritual essence of form and color and its release from imprisonment in the world of objects.1

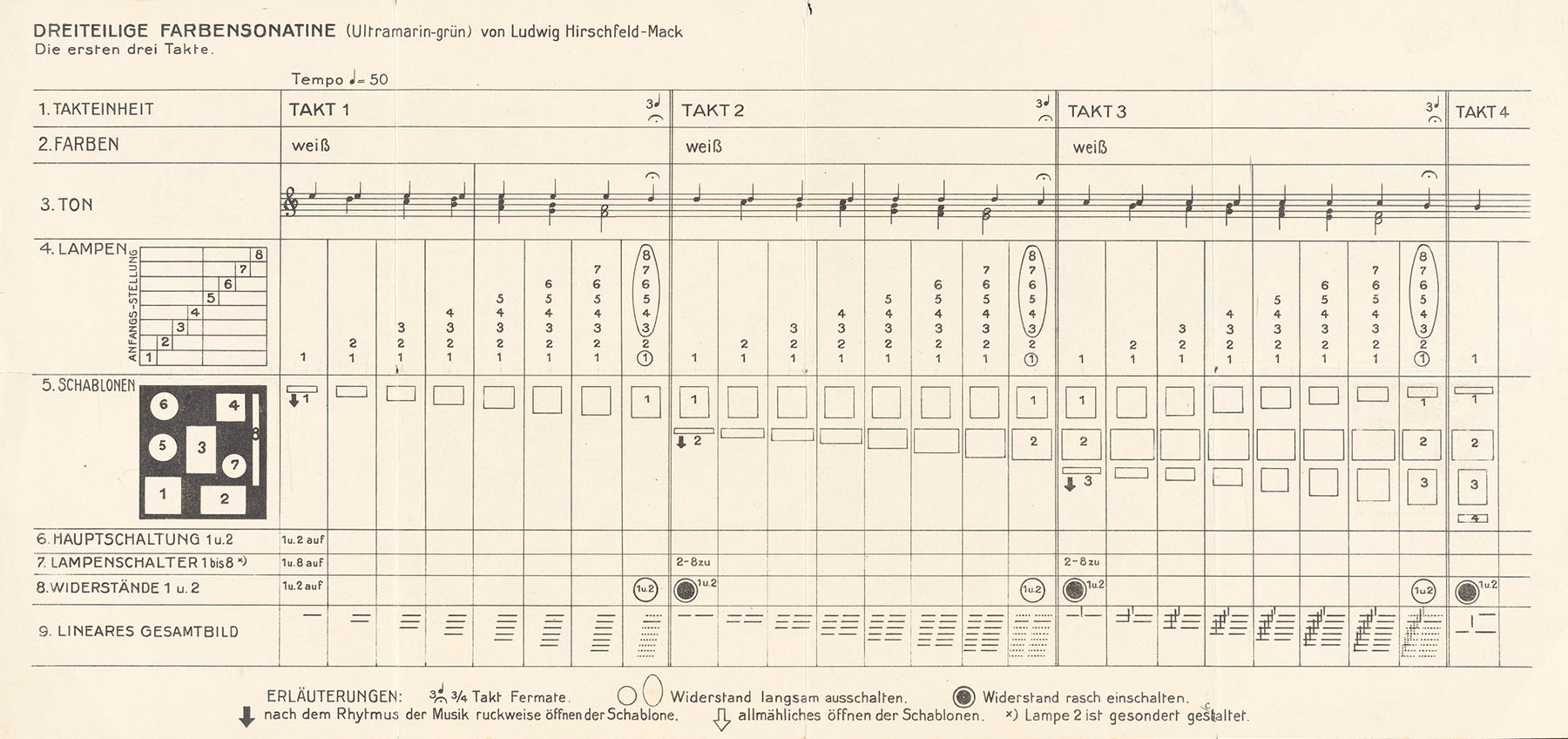

Premiering at the Bauhaus in 1923, student Ludwig Hirschfeld-Mack’s Color-Light Plays (Farben Licht-Spiele) was a dazzling testament to the principles of color and form taught at the Bauhaus. Hirschfeld-Mack described it as “a play of moving yellow, red, green, and blue light fields in organically contingent gradations evolving from darkness to highest luminosity.”2 Leaving paint and materials behind, the performance radically transmuted color and form into pure light.

Color-Light Plays was performed live using mechanically operated colored lights shown through cut paper stencils that cast luminous patterns onto a transparent scrim. These elements were choreographed to music in an attempt to realize the many musical analogies that Bauhaus masters such as Johannes Itten, Vassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, and Josef Albers repeatedly invoked to describe the act of pictorial composition.

Student Ludwig Hirschfeld-Mack’s Color-Light Plays was a mobilization of Bauhaus lessons in form and color, synthesized to unleash the static elements of painting in real time and space.

The experiment was a critical success. Hirschfeld-Mack toured Germany, occasionally joining Kandinsky on the lecture circuit, where Color-Light Plays illustrated Kandinsky’s theoretical principles and their visual effects. In this way, Hirschfeld-Mack’s invention helped convince a wider public that the Bauhaus was an important center for artistic research. But what made his optical tour de force so widely appealing?

Hirschfeld-Mack constructed Color-Light Plays using the basic formal elements found in painting: the point, the line, and the plane. The overall effect was a mobilization of Bauhaus lessons in form and color, synthesized to unleash the static elements of painting in real time and space.

Instruction in form and color began in the first semester of a Bauhaus student’s education and continued in the form of advanced seminars designed to complement workshops. Johannes Itten devised the initial scheme for the Preliminary Course in 1919, and the following year it was enacted as a requisite course for all Bauhaus students. From the outset, specialized subjects in the Preliminary Course were taught by other masters, such as Paul Klee who taught Theory of Design (1921–1924/5) or Vassily Kandinsky who taught Analytical Drawing (1922–1925).

While the roster of course offerings shifted over time as numerous masters stepped in to teach variously themed classes, the overall philosophy remained remarkably consistent from Weimar to Dessau to Berlin: a firm grounding in the principles of form and color achieved through practical exercise was essential to the development of the new artist. Accordingly, form and color were initially studied separately before being considered as they actually appeared—always together, as inseparable elements of pictorial composition.

Notes

- Johannes Itten, The Art of Color (New York: Reinhold Publishing Corporation, 1961), 152. ↩

- Ludwig Hirschfeld-Mack, Farbenlicht-Spiele (Weimar, 1925), 1. (German translation: Ein Spiel bewegter gelber, roter, grüner und blauer Lichtfelder, in organisch bedingten Abstufungen aus der Dunkelheit entwickelt bis zur höchsten Leuchtkraft). ↩

What shape is color?

Explore the Kandinsky Form and Color Exercisenavigate_next| words