History of the Bauhaus

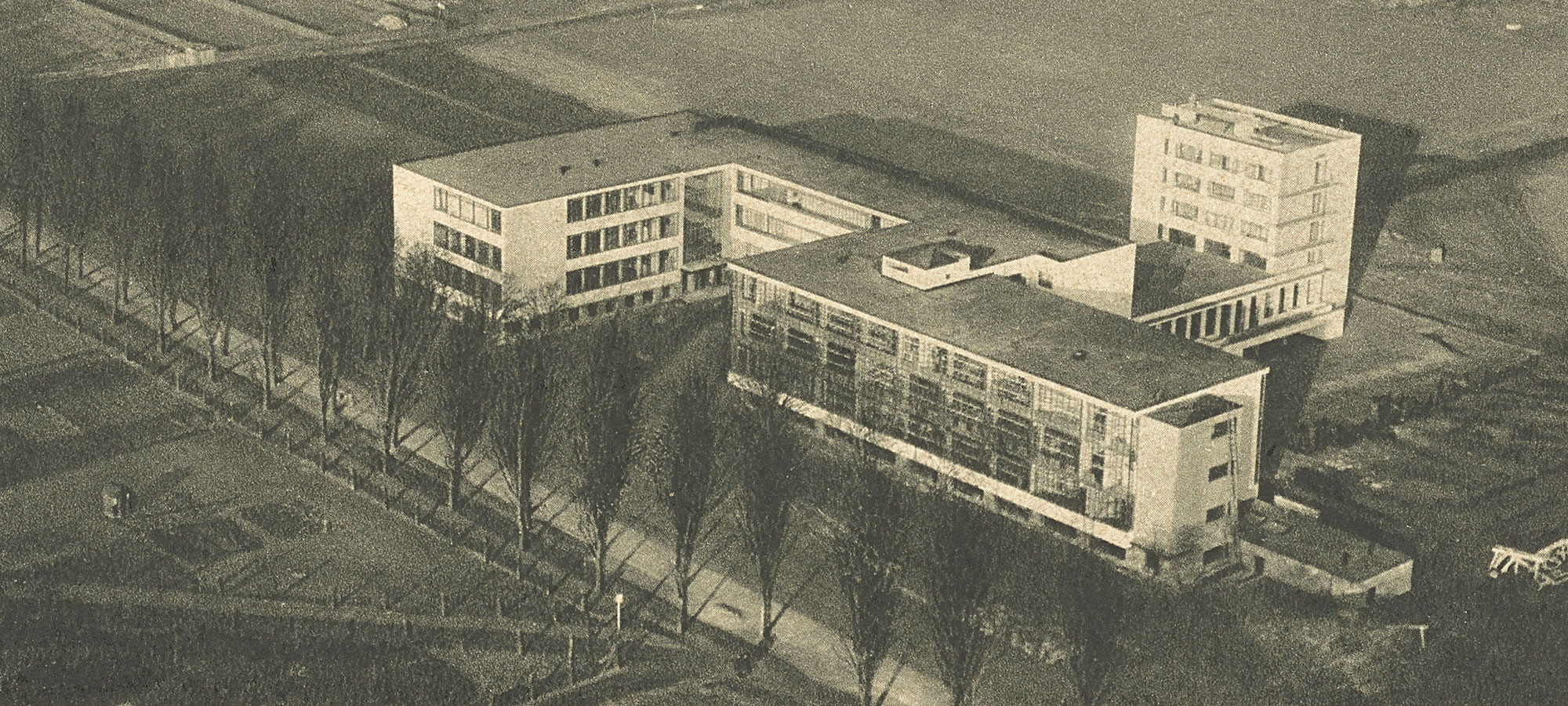

Fig. 1. Postcard sent to Jan Tschichold with aerial photograph of Bauhaus Dessau. Building: Walter Gropius, 1926. Photo: Junkers Luftbild, 1926. Gelatin silver print on postcard. 10.5 x 14.7 cm. Jan and Edith Tschichold Papers, 1899–1979. The Getty Research Institute, 930030

Art and the people must form an entity … The aim is an alliance of the arts under the wing of great architecture.1

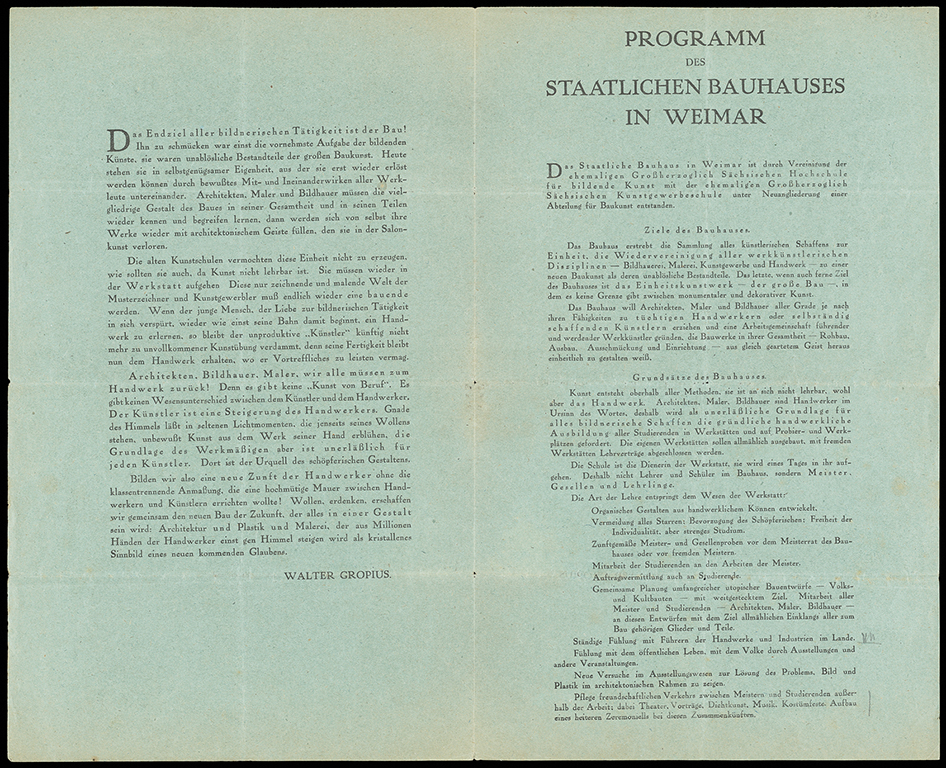

Following the end of World War I, the provisional government of the short-lived Free State of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach in Germany initiated an effort to reestablish two schools, the Weimar School of Applied Arts (Weimar Kunstgewerbeschule) and the neighboring Academy of Fine Arts (Hochschule für bildende Kunst), as a single, unified institution. Upon the recommendation of Belgian architect Henry van de Velde, who had previously directed the Weimar School of Applied Arts, the Berlin architect Walter Gropius was invited to head the new school. Gropius’s request to rechristen the institution under a new name, Bauhaus State School (Staatliches Bauhaus), was approved in March 1919.

The school officially opened on April 1, 1919. In a rousing manifesto laced with mystical analogies between creative production and spiritual awakening, Gropius set forth a vision for a new model of education that would unite the divisions between the fine and the applied arts. The director hoped that various forms of artistic practice—painting, sculpture, architecture, and design chief among them—could work in harmony at the new school to produce the socially oriented and spiritually gratifying “building of the future.”2

Architecture promised the possibility of realizing the total work of art, in which designers, artists, and artisans worked together toward a single, spiritual goal.

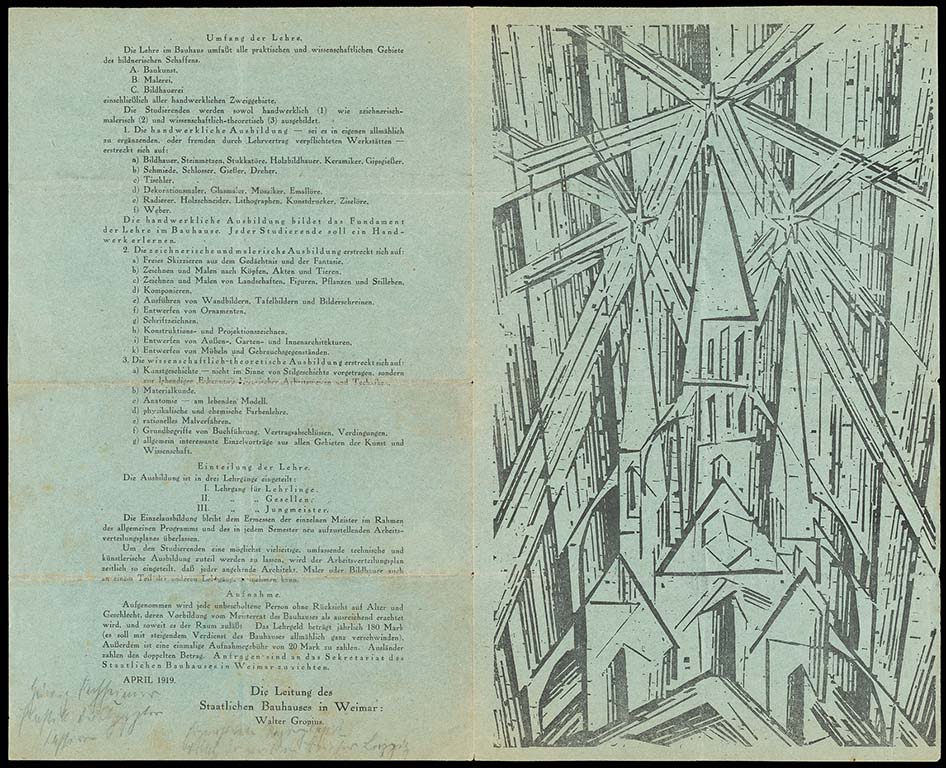

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.Gropius asked one of the earliest figures to be hired at the Bauhaus, the painter Lyonel Feininger, to graphically evoke the spiritual possibilities of this new art pedagogy. Feininger illustrated Gropius’s future-oriented vision somewhat counterintuitively with a woodcut image of a gothic cathedral replete with flying buttresses, pointed arches, and rays of light emanating from its steeples. A preindustrial building form, the cathedral promised the possibility of realizing the Gesamtkunstwerk, or the total work of art, in which designers, artists, and artisans worked together toward a single, spiritual goal.

Gropius’s radical pedagogical vision subjected the school to considerable political pressure throughout its short life, particularly from the increasingly conservative forces that took hold in Weimar Germany. For this reason, the school was forced to relocate from Weimar to Dessau in 1925, and then from Dessau to Berlin in 1932. The school’s demise came at the hands of the Nazis in 1933. Despite continual turmoil throughout the Bauhaus’s itinerant existence, its radical pedagogy cemented the school’s legacy as a site for artistic experimentation well into the 21st century.

From the 1919 Program

The ultimate goal of all creative activity is the building! To decorate the building was once the noblest function of the fine arts, and the fine arts were considered indispensable components of great architecture. Today they exist in complacent isolation, from which they can only be delivered by the conscious collaboration and cooperation of all craftsmen. Architects, painters, and sculptors must recognize anew and learn to grasp the composite character of building, both as a totality and in terms of its parts so that their work may once more imbue itself with the architectonic spirit, which it lost in salon art.

The old art schools were incapable of producing this unity—and how could they, for art cannot be taught. They must be merged once more with the workshop. This world of mere drawing and painting of pattern-designers and applied artists must at long last become a world that builds. If the young person who senses within himself a passion for creative practice begins his career, as in the past, by learning a trade, then the unproductive ‘artist’ will no longer be condemned to imperfect artistry because his skill will be preserved in craftsmanship, where he may achieve excellence.

Architects, sculptors, painters, we all must return to the crafts! For there is no such thing as ‘art by profession.’ There is no essential difference between the artist and the craftsman. The artist is an exalted craftsman. Merciful heaven, in rare moments of illumination beyond man’s will, may allow art to unconsciously blossom from the work of his hand, but the foundations of craft are indispensable to every artist. This is the original source of creative design.

So let us then create a new guild of craftsmen, free of the divisive class pretensions that attempted to raise an arrogant barrier between craftsmen and artists! Let us together will, conceive, and create the new building of the future, which will unite everything in a single form—architecture and sculpture and painting—and which will one day rise heavenwards from the hands of a million craftsmen as a crystalline symbol of a new and coming faith.3

–Walter Gropius

Notes

- Walter Gropius, César Klein, Adolf Behne, et al., program of the Arbeitsrat für Kunst Berlin (Workers’ Council for Art Berlin), March 1, 1919, n.p. ↩

- Walter Gropius, Programm des Staatlichen Bauhauses in Weimar, trans. Katherine Rochester (Weimar: Staatliche Bauhaus, April 1919), n.p. (German translation: Bau der Zukunft) ↩

- Ibid. (German translation: See fig. 5) ↩

| words