Masters and Apprentices

Walter Gropius was asked in early 1919, at the age of 35, to lead the new school of art and design in Weimar. Earlier in the decade, he had established himself as a leading modernist architect committed to languages of rationalism and the burgeoning “machine aesthetic,” with explicit influences stemming from factory architecture and processes of industrial standardization. The unprecedented horrors of mechanized warfare that he experienced in World War I, however, forced the young architect to rethink his commitment to rationalism and industry. By 1919 Gropius had become increasingly focused on exploring the possibilities of romanticism, Expressionism, and socialism in architecture.

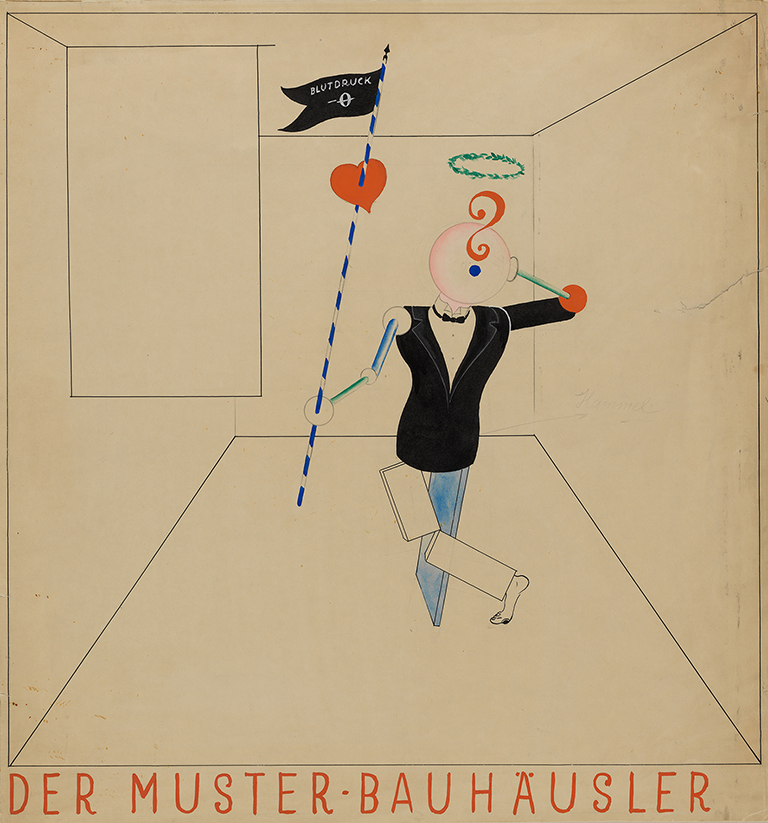

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.As the head of the newly established Bauhaus, Gropius recruited major, international figures associated with prominent artistic groups in Germany—such as Der Blaue Reiter in Munich and Der Sturm in Berlin—and members of the Russian avant-garde to teach at the school. Reflecting both his turn to Expressionism and his commitment to bringing together diverse disciplines, Gropius’s earliest recruits included artists Lyonel Feininger, Johannes Itten, Gerhard Marcks, and Gertrud Grunow. In the following years, Gropius hired other leading artists such as Paul Klee, Oskar Schlemmer, and Vassily Kandinsky. Though these figures were in large part committed to the production of art objects, it was Gropius’s conviction that a revolutionary form of spiritual expression should not be constrained to the domain of fine art; he sought instead to imbue objects of everyday life with an artistic spirit, too.

Gropius’s ambition was nothing less than to forge a new type of artist.

Walter Gropius’s vision for creating “a new guild of craftsmen” was not restricted to the painting of artworks or the design of everyday objects.1 The first students who arrived at the Bauhaus were confronted by a peculiar provision outlined in the school’s program. One of its key principles dictated that students participate in extracurricular activities such as “theater, lectures, poetry, music, [and] costume parties,” at which they were expected to contribute to a “light-hearted” or “cheerful” atmosphere.2 Students not only lived and dined together but also spent their free time playing sports, designing publications, organizing parties and festivals, and collaborating on art projects. Parties at the Bauhaus were legendary and often elaborately themed, involving sets and costumes that required expertise from the workshops.

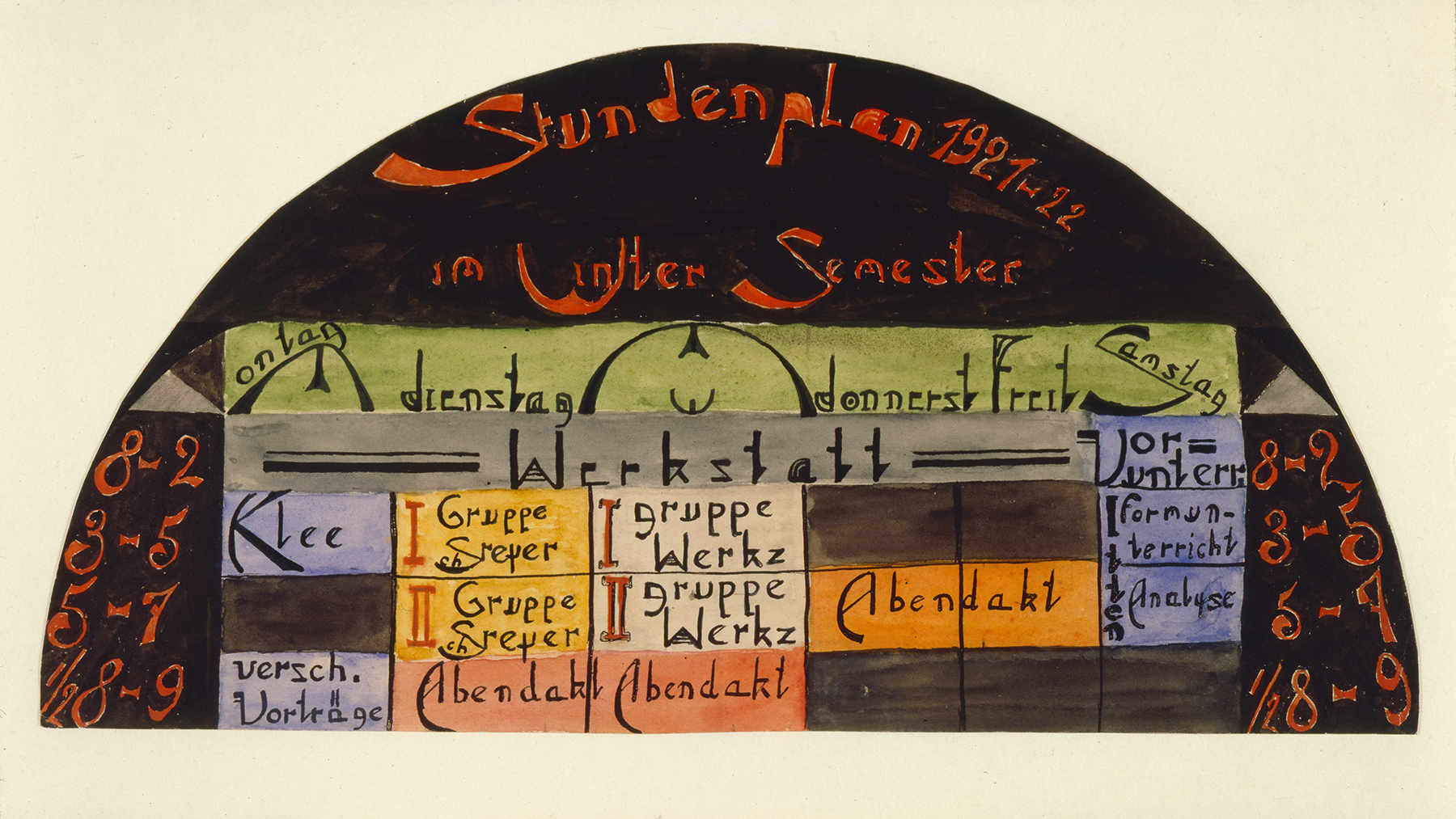

Fig. 10.

Fig. 10. Fig. 11.

Fig. 11.In keeping with Gropius’s romantic, preindustrial vision for modern arts education at the Bauhaus, the school’s structure followed a medieval guild model of labor organization. The majority of professors were deemed “masters,” while students were known as “apprentices” or “journeymen,” with a distant promise of graduating to the status of “junior master.” At Gropius’s insistence, students at the Bauhaus comprised a relatively diverse group in terms of age, gender, and nationality. His ambition was nothing less than to forge a new type of artist. A number of students educated at the Bauhaus became leading masters and influential teachers at the school: among them were Anni Albers and her husband Josef Albers, Herbert Bayer, Marianne Brandt, Marcel Breuer, Xanti Schawinsky, Joost Schmidt, and Gunta Stölzl.