Learning with Albers

Albers joined the Bauhaus as a student in the Summer semester of 1920. Three years later he became the first pupil to assume a teaching position at the school when Gropius appointed him to lead the introductory section of the Preliminary Course. In subsequent semesters he also took over teaching Material and Tool Theory (Material-und Werkzeuglehre).

A passionate pedagogue, Albers challenged and inspired his students by establishing strict parameters for exercises and then encouraging them to work through problems on their own. “In Albers’ classroom,” recalled a student, “nothing was presumed to be known, everything had to be self-sought, discovered, analyzed and represented, so that it would truly be one’s own.”1

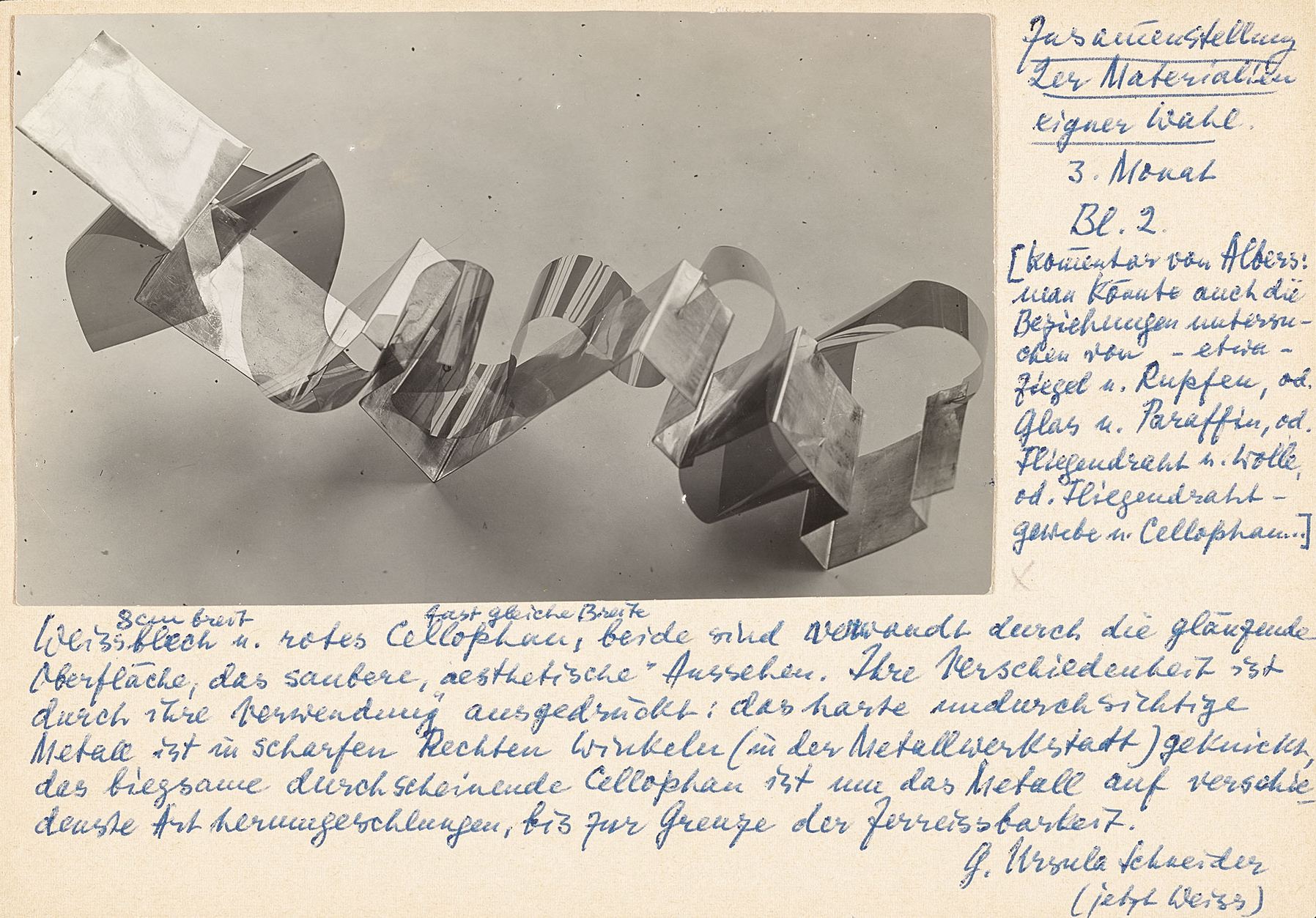

Albers’s matter studies were similar to Itten’s in that they involved the combination of various materials to explore properties in relation to one another. These exercises focused on surface structure, facture, and texture. Contrasts could be subtle or glaring, depending on the materials chosen and their handling (facture). Here, students might use materials to mimic other materials by trying, for example, to make paper look like velvet or bark like cloth.

Fig. 43.

Fig. 43.A series of annotated notebook pages (figs. 42, 43) shows two examples of matter studies from Albers’s course. Student Ursula Schneider’s study in metal and red cellophane revealed a correspondence between their “shining surface” and their “clean ‘aesthetic’ appearance.” However, their difference was highlighted in the rigid angles of the metal and the curving waves of the cellophane: “The hard, opaque metal is folded in sharp right angles (in the metal workshop), the flexible translucent cellophane is wrapped around the metal in various ways, up to the limit of tearing.”

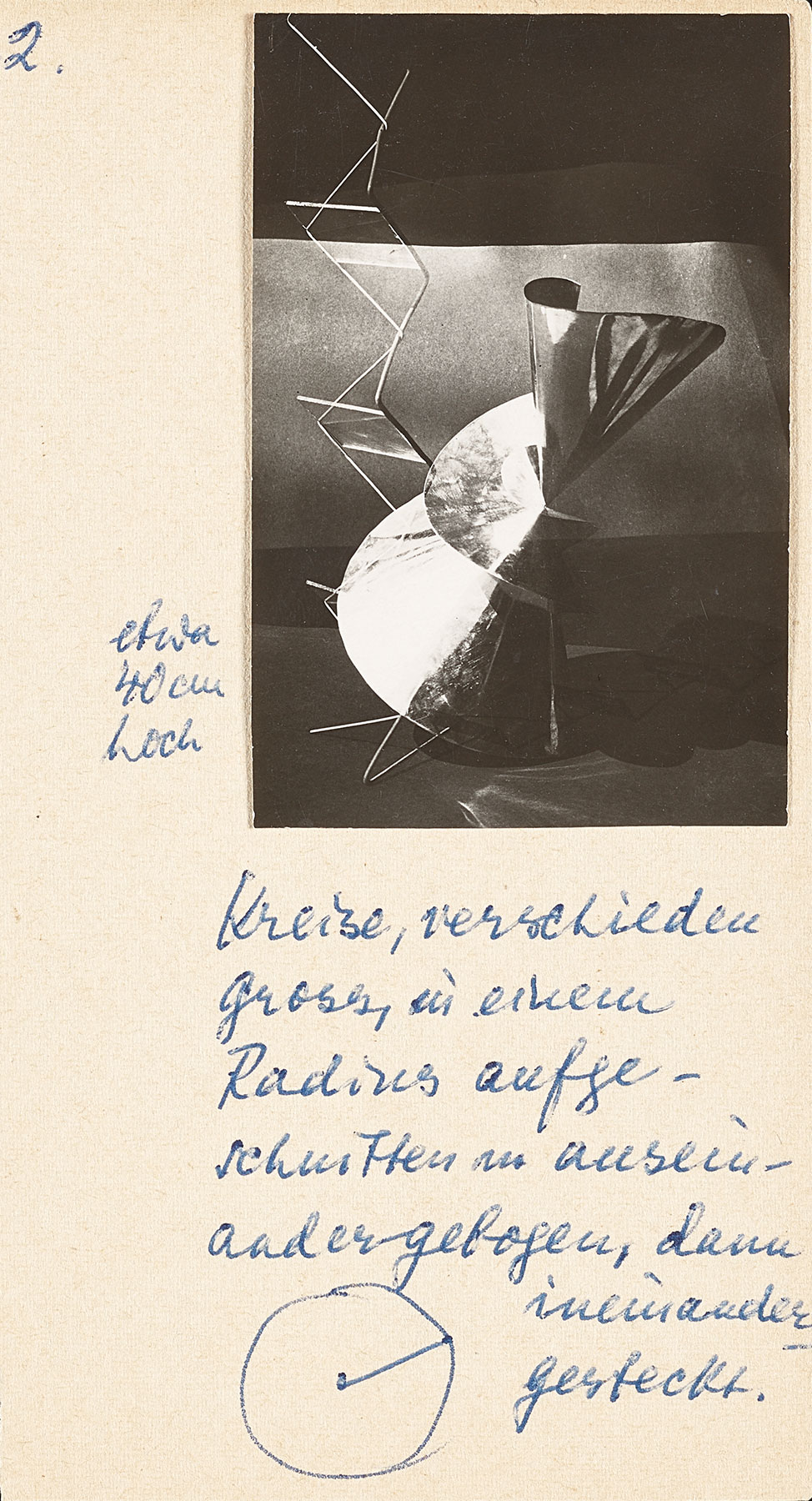

The other study is a balancing exercise. Student Lotte Gerson assembled hers from the glass neck of a lamp through which she suspended a spiral cut from a cellophane bag. According to her note, the bag had held clippings from haircuts in the women’s bathroom, a “radical break with bourgeois traditions!”

Albers instructed students to express one clear formal idea using the internal quality and inherent structure of a given material. Glue was not allowed.

Fig. 45.

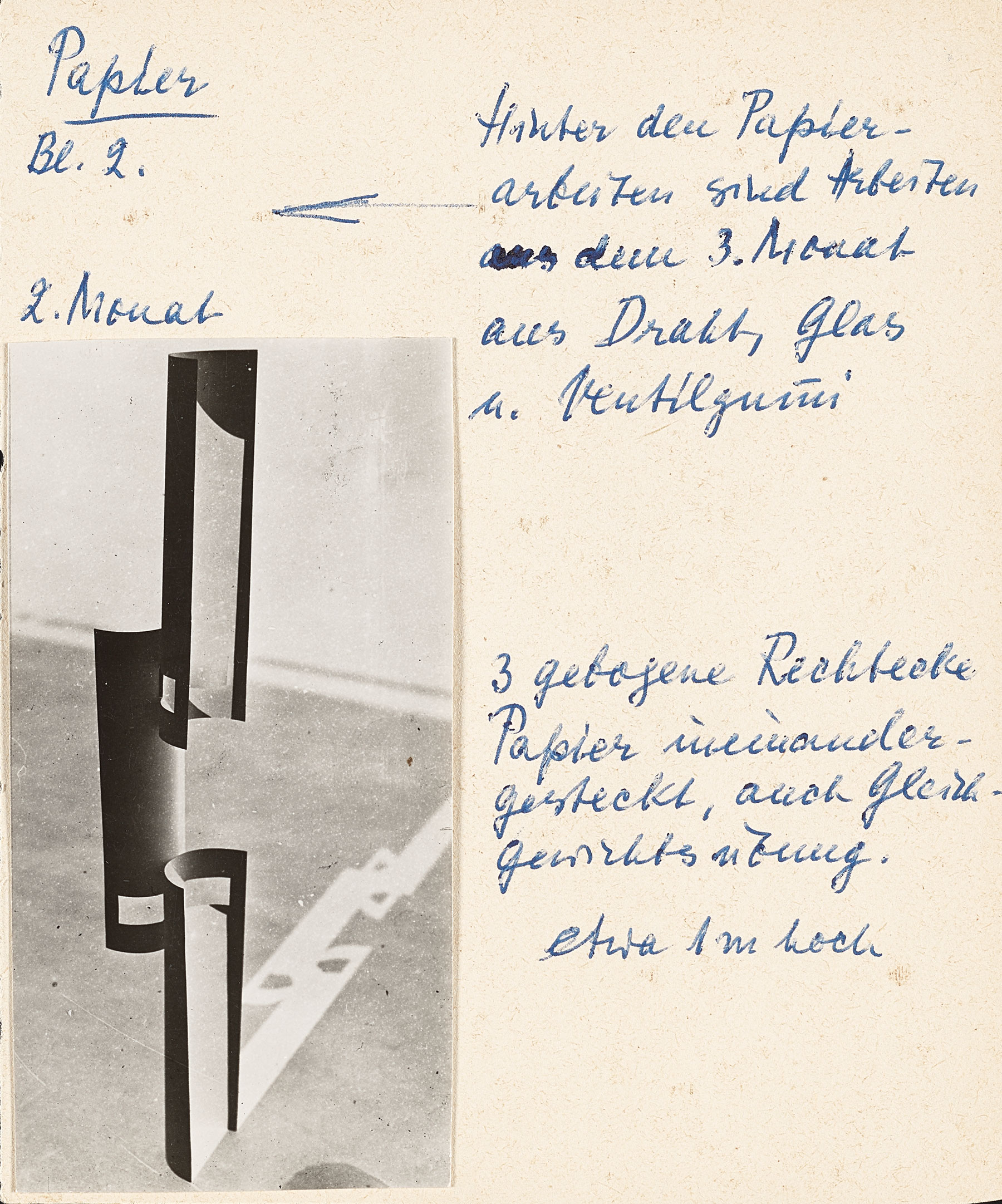

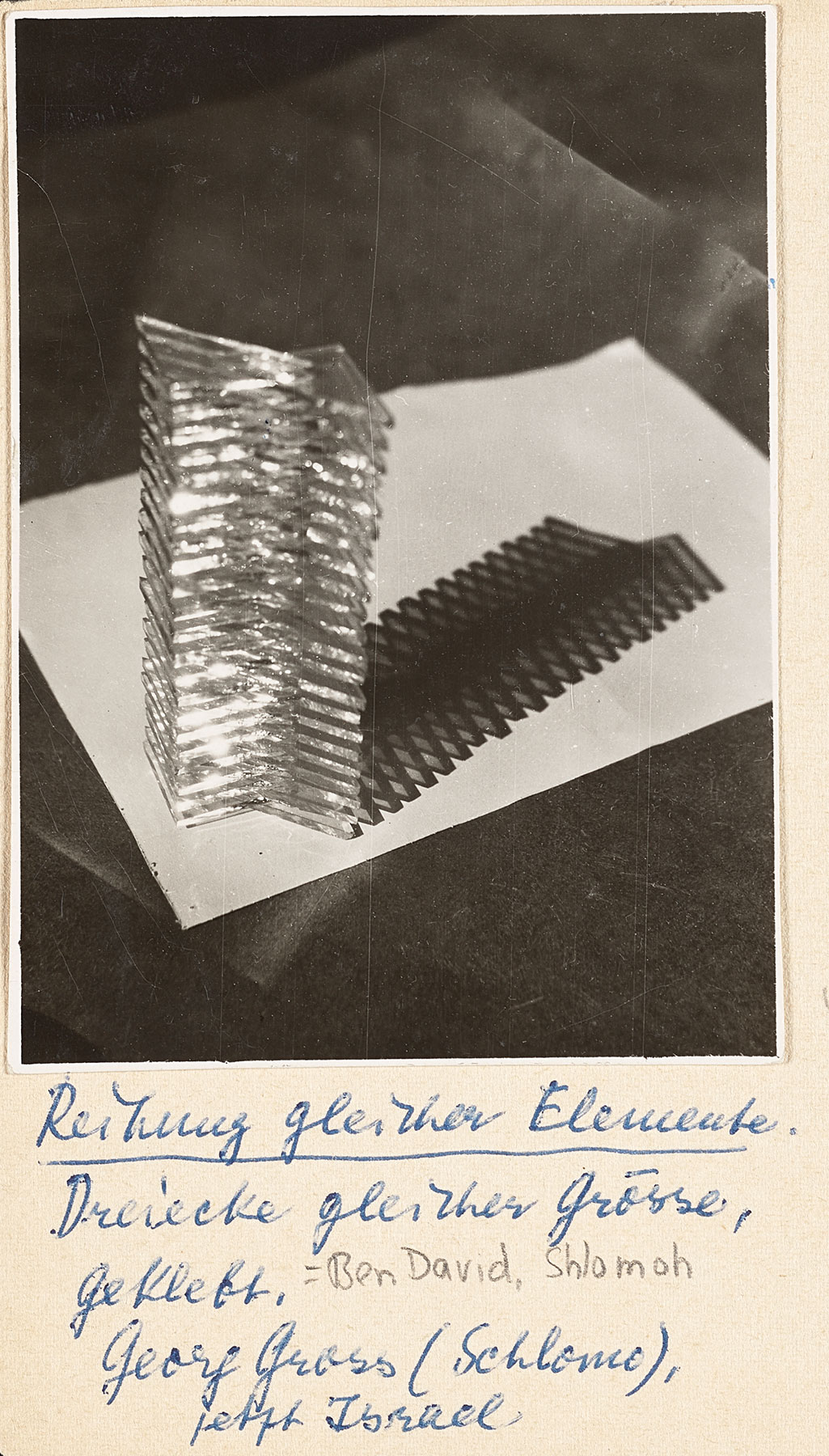

Fig. 45.Material studies, as in the examples pictured, were restricted to a single material. Albers instructed students to express one clear formal idea using the internal quality and inherent structure of a given material. Glue was not allowed. Forms should adhere to one another through balance and pressure. Students were instructed to use found materials, though not objets trouvés such as Itten’s student’s Maggi label, which had already been formed into a certain shape for a certain purpose and therefore carried with it certain associations.

A key term for Albers was “material integrity” (Materialgerecht), as demonstrated by student Takehiko Mizutani’s metal disc assemblage (fig. 44), which wedges discs into premade slots in the metal. George Groß stacked “a sequence of similar elements” in his glass experiment for Albers (fig. 45), while an anonymous student’s work (fig. 46) from the second month of the Preliminary Course consisted of a balancing exercise made of interlocking paper rectangles.

Notes

- Vera Meyer-Waldeck, “Dank an Josef Albers,” in Werk und Zeit, vol. 7, no. 12 (1958), 3. ↩